What do you need to truly recover from grief? The Grief Recovery Handbook answers that question in a thorough, powerful, practical way.

As we’ve decorated our Christmas tree, baked, and shopped for gifts, I’ve thought a lot about my parents. They were devout Episcopalians, and over the years they observed Advent and Christmas with both spiritual devotion and genuine delight in the more secular traditions like gift-giving and cookie painting.

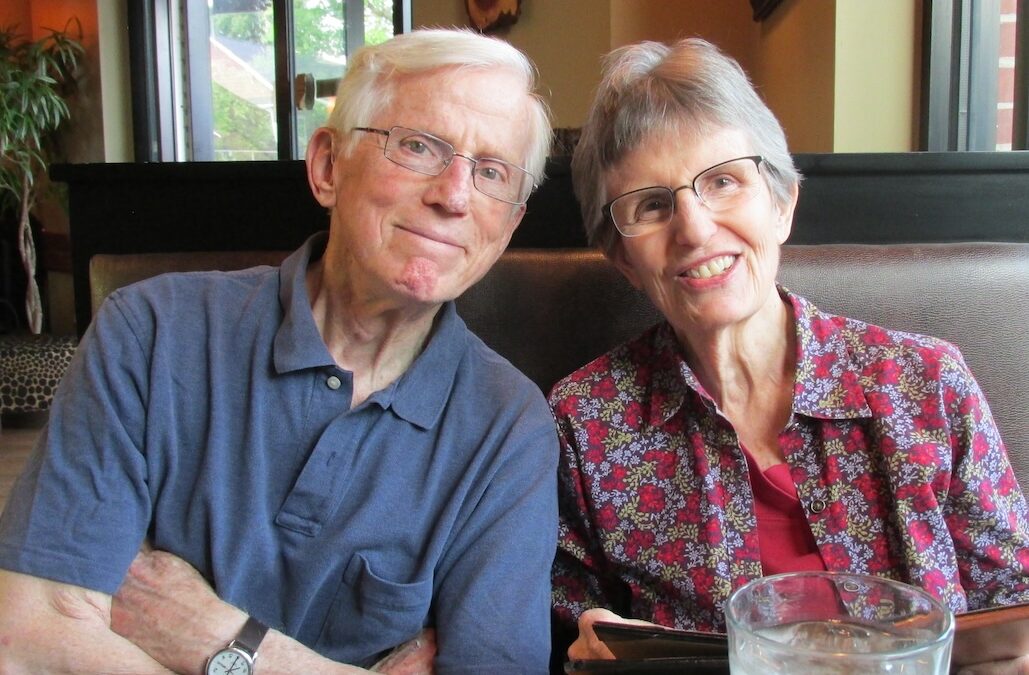

Dad died nearly three years ago, Mom eight months ago. I’m still struggling to take in that they are gone. Carrying on without them, I’ve felt a complex and changing mix of emotions: grief, joy, sadness, regret, gratitude, and more.

The hardest part for me about grieving has been the feelings of incompleteness I’ve encountered. This includes things I wish I’d said, but didn’t, along with things I didn’t say that I wish I had said. I had never heard of the concept of completing grief until I read a small, purple-jacketed book called The Grief Recovery Handbook, by John W. James and Russell Friedman.

I’ve been wanting for some time to write an appreciative book review for you of the Handbook, because the Grief Recovery Method has been so helpful to me. (I’m not affiliated with the organization: I’m just writing as myself, a consumer.) All of us carry grief, simply because being alive involves loss, and HSPs feel it with our typical intensity.

Although I’ve “completed” only two losses so far—my dad and my mom—I’ve been struck by the relief I’ve experienced already. In addition to the completion itself, I feel relieved knowing I now have skills and understanding of grief that will enable me to reach a sense of completion around a number of other losses I have experienced in my life: obvious losses like death and divorce, and also less obvious ones like the end of my music career.

Understanding grief

James and Friedman offer a two-part definition of grief:

- The normal and natural reaction to loss of any kind, and

- The conflicting feelings caused by the end of or change in a familiar pattern of behavior.

These simple sentences helped me understand my reactions to loss in an entirely new way. Now, I understand that grief is not a single feeling. When Mom died, for example, I felt relief on one level, knowing how much physical and emotional pain she had been suffering and how much she just wanted to be done with it. But I was also shocked thinking of the violent fall she’d taken, and I felt (and still feel) bereft.

Similarly, now that I understand that changes in a familiar pattern of behavior can cause a complex array of feelings, I more easily recognize events and situations that I need to grieve. On the Tuesday just before Thanksgiving, my son remarked that it felt strange not to be driving to the Red Roof just north of Cleveland. We’d always stop there on our way to Indiana for Thanksgiving with my parents and (randomly but regularly) watch “Dancing with the Stars” on the motel TV. I felt oddly disoriented, realizing there was a last time we made that trip, and that we may never make it again: a poignant change in a familiar pattern of behavior.

Whatever your grief looks or feels like, you need an effective way to process it. Given the intensity and complexity of our emotions, highly sensitive people (HSPs) in particular need effective ways to process grief—or, as James and Friedman would say, to complete our grief. The program is based on their realization, processing their own terrible losses, that what they needed was somehow to complete those losses.

About the process

The Handbook—or the Grief Recovery Method classes, which you can take online or in person—goes through the completion process in detail. The language is clear, and the instructions are deceptively simple. They’ve done the process with thousands of people and have found it works if you follow it faithfully. That has been my experience.

You can’t just read about grief recovery. You have to do every step. It is a deep process, and it takes time and emotional energy. You explore the beliefs you learned about from your family, identify the coping mechanisms you use to deal with grief, and make a loss graph of all the losses you’ve experienced in your life. Then you make your first relationship graph for a specific person with whom you feel incomplete—that is, stuck in a place of wishing things could have been “different, better, or more.” You organize the contents of your graph into categories, then use them to write a very specific kind of letter to the person you are grieving.

Each time you complete a step, you meet with your Grief Recovery partner. (I first did it with a friend who is also one of my focusing partners. Then, this fall, I did eight sessions with a Grief Recovery instructor in person here, which was really helpful.) You pledge confidentiality, then take turns reading out what you’ve written. Your partner listens without comment. I’ve found the process very emotional. I’m always tired after a meeting, but in a good, cleaned-out sort of way.

What was the result?

I got significant relief the first time I did the process about my dad. However, when I worked with the Grief Recovery facilitator in person this fall, I decided to go through my relationship with Dad again. I understood the process on a deeper level this time, and I have experienced much deeper relief.

Before I “completed” this loss, the pain I felt about some tough things that happened with my dad was blocking me from truly savoring all the wonderful things about him. I felt guilty, too, because there were a lot of wonderful things. I had a voice saying, “What is your problem? Let it go. Focus on the good stuff.” Now, that inner conflict is gone. The painful things have lost their “sting.” I can hold the whole relationship in my heart: the painful things that happened, and the wonderful things.

If you are carrying unresolved grief, consider giving yourself the gift of this process for completing it. As the authors of the Handbook explain,

Unresolved grief consumes tremendous amounts of energy. Most commonly, the grief stays buried under the surface, and only the symptoms are treated. Many people, including mental health professionals, misunderstand the fact that unresolved loss is cumulative and cumulatively negative.

Now that I understand that, I’m inspired to take more and more rocks out of my emotional backpack. I will go on to “complete” several other relationships and losses in my life.

Possible next steps

I have gotten a lot from working individually with a Grief Recovery facilitator. As with any 1:1 work, you need to find someone you trust, with whom you feel comfortable sharing in a vulnerable way. I haven’t taken a Grief Recovery class online, but I’ve heard they are very effective.

By coincidence, I got an email this week from the Grief Recovery Institute, saying they are offering the audio version of the Handbook for free right now: click here to download it. If you’re going to work through the process, you’ll definitely want a hard copy for easy reference. However, the audio book could be an easy way to begin to familiarize yourself with this method, and it’s the kind of book you’ll end up reading several times anyway as you work through it.

Note: Thanks to my sister for the photo of Mom and Dad.

I’m sorry to hear about the loss of your mom Emily, my heart goes out to you and your family. As you know I lost my dad just over a year ago and we had a complicated relationship. While I feel mostly at peace with it, I’m still curious about what might be hiding and I’m thankful you shared the Grief Recovery Method Handbook. I look forward to trying it out and seeing what I might learn from it.